Have you ever been witness to a rear-end collaboration? It isn't pretty and the traffic slows to a crawl with no clear reason why a perfectly smooth ride turns into a gaggle of abandoned bumper cars in the breakdown lane.

The rear-end refers less to orifice that we use to insult the bad collaboration actors. It's not even about going stealth or secretive in the one-way exchange of participation-free online lurkers in the shadows of online collaborations. It's really more about fear of being perceived as an ass than any backwards thinking now in vogue. It's more about standing out for the wrong reasons. It's an anxious place where the reward for participation is the absence of penalties.

Some of us like to stand out. Most of us would rather pick the time and the place. In the age of closed circuit camera phone reality exceedingly few of us see any form of personal recognition as positive recognition.

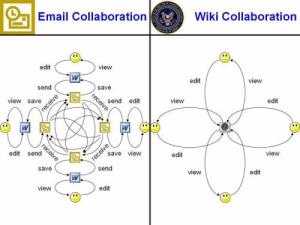

It's that bridge from stilted collaboration to the exquisite melding of group minds that we crossed over at last Thursday's meeting of Boston's SIKM chapter. Sometimes it was about wikis or listservs or task-based or even competitive collaboration. But in each case we all took in the collective smell test and passed our own versions of what's applicable to our own teams and projects. We also played bumper cars in a freewheeling, agenda-defying forum. I don't remember any drivers slowing down to inspect the damage.

My favorite part of this meeting was that the majority had no prior SIKM meetings from their calendars. The notion that we could all steer the same rudder over two hours of unscripted ideation was the glue that held our experiences up to the light of peer review. Unimpeded by PowerPoint and the flimsiest of agendas, the most contestable of assertions was made by Ken Cundari: that the road to bad collaboration is paved with riffing on ideas untethered to concrete tasks and goal-setting.

The rear-end refers less to orifice that we use to insult the bad collaboration actors. It's not even about going stealth or secretive in the one-way exchange of participation-free online lurkers in the shadows of online collaborations. It's really more about fear of being perceived as an ass than any backwards thinking now in vogue. It's more about standing out for the wrong reasons. It's an anxious place where the reward for participation is the absence of penalties.

Some of us like to stand out. Most of us would rather pick the time and the place. In the age of closed circuit camera phone reality exceedingly few of us see any form of personal recognition as positive recognition.

It's that bridge from stilted collaboration to the exquisite melding of group minds that we crossed over at last Thursday's meeting of Boston's SIKM chapter. Sometimes it was about wikis or listservs or task-based or even competitive collaboration. But in each case we all took in the collective smell test and passed our own versions of what's applicable to our own teams and projects. We also played bumper cars in a freewheeling, agenda-defying forum. I don't remember any drivers slowing down to inspect the damage.

My favorite part of this meeting was that the majority had no prior SIKM meetings from their calendars. The notion that we could all steer the same rudder over two hours of unscripted ideation was the glue that held our experiences up to the light of peer review. Unimpeded by PowerPoint and the flimsiest of agendas, the most contestable of assertions was made by Ken Cundari: that the road to bad collaboration is paved with riffing on ideas untethered to concrete tasks and goal-setting.

My contention is that dynamic applies to teams but not individuals. That's because this model puts motive in the spotlight. Most clients desire outcomes devoid of their own personal reasons for wanting it. Yes, productivity unmasks the poker face when the same team is playing to win with the same playbook. But the productivity argument falters under the weight of the fuller disclosure that a stated purpose requires. Besides, I (client) will pay more if you (consultant) really know the worth of your deliverable.

Laurie Damianos and Lester Holtzblatt also contributed some firsthand feedback on their own user communities, including the insight that would-be wiki collaborators need to know the circulation numbers (ocean wiki or pond-sized wiki) before they take the plunge.

Based on the steady stream of inputs from our collective exchange it seems the improvised brainstorming and the orchestrated roadmapping blended into one. To my best recollection here are the testifiers:

Patti Anklam

Patti Anklam