In the scheme of qualifications, I'm not qualified to be very much. But I am an authority on the question of how humans and search engines tend to talk over one another when they share the same screen.

Here it is -- the number one communicado non-starter. We over-specify what we want when we talk with search engines. We want it so bad we expect to bear witness to its materialization on our doorsteps and driveways. For commerce this works out fine. I want a size XXL horsepower in the original casing and want it to hit my cash rewards program before the arrival of my free shipping. But then it falls to fragmented pieces:

- It's not an exact match of fallen-out-of-Facebook-is-this-Sally-really

- It's not the exact place and time the package was designed to arrive

- It's not the exact same set of challenges you expected to be up against the next time

If there's only one-of-a-kind out there, we have an infinite loop of errors that send us to the land of the correctionless -- the placeholder Google's algorithm has reserved for our habitation. Are we surprised? Is an ulcer coming on? Perhaps, then our surprise should be worn and not masked? That's how we remember why we Googled in the first place. No chicken-and-egg problem about that. It has to do with yanking our minds out of our rabbit holes. It's about seeing the world from a broader perspective than our in-boxes and portfolios.

This tendency to over-specify is not our proudest achievement as disgruntled Googlers. It's really the natural extension of our need to dumb reality down for the sake of simplicity. It's not that we can't absorb the complexities. It's that we want a clear set of instructions. We want to be told what to do. That's not going to happen without a price, a catalog, and the certainty of a transaction about to happen.

For capital goods and tangible services we either share an understanding or will come to one. For everything else we have our own hunches or the eerie suspicion that we can't find what we're looking for. The hope is not for better search technology but for the ability to think more abstractly in order to expand a useful range of outcomes. This reminds me of the search troubles of some former PI students. Some were comfortable with directories and specialty databases for scouring public records. Others never left their search boxes, repeating the names of the same criminal suspects and eliciting the same three hits from the same three thousand sites. That's a fixation well worth escaping.

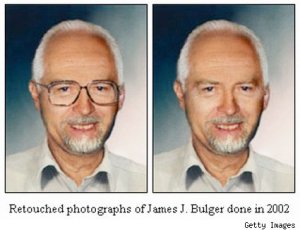

These same search dynamics surround the recently solved capers of our most wanted 1-2 on the post office walls of an American generation. In both cases the criminal was under our unsuspecting noses and free from under our fumbling thumbs. The more wanted they became, the more convinced we seemed were the vanishing tricks played on us by their deceitful legends. But sooner or later the steely resolve of wanted-dead-or-alive gives way to the intricacies of an expanding drag net. There were choice bits of bait on a coterie of lures:

- Was it the delivery man as the whistle-snitch?

- Where in her jam-packed appointment book was the girlfriend penciled in next?

The only way these men could be brought to justice was to meet them out in a cavernous world of their own design. That takes theory of mind, extrapolation, dexterity, and perspective taking. And while we're piling onto what lands well clear of the Google radar, let's remember that sound taxonomy and our own search architectures are our best bet for deploying Google in its non-shopping glory.

This is an abstraction to the average "user." This is something perhaps only a Google "customer" might insist on.